Go 博客

From zero to Go: launching on the Google homepage in 24 hours

2011/12/13

Introduction

This article was written by Reinaldo Aguiar, a software engineer from the Search team at Google. He shares his experience developing his first Go program and launching it to an audience of millions - all in one day!

I was recently given the opportunity to collaborate on a small but highly visible "20% project": the Thanksgiving 2011 Google Doodle. The doodle features a turkey produced by randomly combining different styles of head, wings, feathers and legs. The user can customize it by clicking on the different parts of the turkey. This interactivity is implemented in the browser by a combination of JavaScript, CSS and of course HTML, creating turkeys on the fly.

Once the user has created a personalized turkey it can be shared with friends and family by posting to Google+. Clicking a "Share" button (not pictured here) creates in the user's Google+ stream a post containing a snapshot of the turkey. The snapshot is a single image that matches the turkey the user created.

With 13 alternatives for each of 8 parts of the turkey (heads, pairs of legs, distinct feathers, etc.) there are more than than 800 million possible snapshot images that could be generated. To pre-compute them all is clearly infeasible. Instead, we must generate the snapshots on the fly. Combining that problem with a need for immediate scalability and high availability, the choice of platform is obvious: Google App Engine!

The next thing we needed to decide was which App Engine runtime to use. Image manipulation tasks are CPU-bound, so performance is the deciding factor in this case.

To make an informed decision we ran a test. We quickly prepared a couple of equivalent demo apps for the new Python 2.7 runtime (which provides PIL, a C-based imaging library) and the Go runtime. Each app generates an image composed of several small images, encodes the image as a JPEG, and sends the JPEG data as the HTTP response. The Python 2.7 app served requests with a median latency of 65 milliseconds, while the Go app ran with a median latency of just 32 milliseconds.

This problem therefore seemed the perfect opportunity to try the experimental Go runtime.

I had no previous experience with Go and the timeline was tight: two days to be production ready. This was intimidating, but I saw it as an opportunity to test Go from a different, often overlooked angle: development velocity. How fast can a person with no Go experience pick it up and build something that performs and scales?

Design

The approach was to encode the state of the turkey in the URL, drawing and encoding the snapshot on the fly.

The base for every doodle is the background:

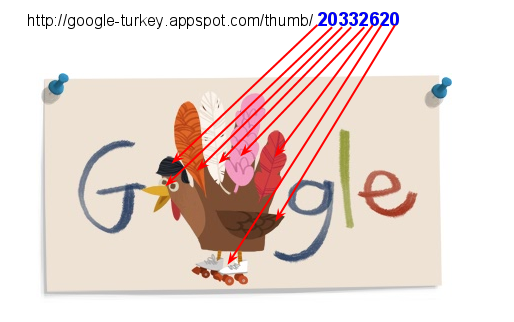

A valid request URL might look like this: http://google-turkey.appspot.com/thumb/20332620][http://google-turkey.appspot.com/thumb/20332620

The alphanumeric string that follows "/thumb/" indicates (in hexadecimal) which choice to draw for each layout element, as illustrated by this image:

The program's request handler parses the URL to determine which element is selected for each component, draws the appropriate images on top of the background image, and serves the result as a JPEG.

If an error occurs, a default image is served. There's no point serving an error page because the user will never see it - the browser is almost certainly loading this URL into an image tag.

Implementation

In the package scope we declare some data structures to describe the elements of the turkey, the location of the corresponding images, and where they should be drawn on the background image.

var (

// dirs maps each layout element to its location on disk.

dirs = map[string]string{

"h": "img/heads",

"b": "img/eyes_beak",

"i": "img/index_feathers",

"m": "img/middle_feathers",

"r": "img/ring_feathers",

"p": "img/pinky_feathers",

"f": "img/feet",

"w": "img/wing",

}

// urlMap maps each URL character position to

// its corresponding layout element.

urlMap = [...]string{"b", "h", "i", "m", "r", "p", "f", "w"}

// layoutMap maps each layout element to its position

// on the background image.

layoutMap = map[string]image.Rectangle{

"h": {image.Pt(109, 50), image.Pt(166, 152)},

"i": {image.Pt(136, 21), image.Pt(180, 131)},

"m": {image.Pt(159, 7), image.Pt(201, 126)},

"r": {image.Pt(188, 20), image.Pt(230, 125)},

"p": {image.Pt(216, 48), image.Pt(258, 134)},

"f": {image.Pt(155, 176), image.Pt(243, 213)},

"w": {image.Pt(169, 118), image.Pt(250, 197)},

"b": {image.Pt(105, 104), image.Pt(145, 148)},

}

)The geometry of the points above was calculated by measuring the actual location and size of each layout element within the image.

Loading the images from disk on each request would be wasteful repetition, so we load all 106 images (13 * 8 elements + 1 background + 1 default) into global variables upon receipt of the first request.

var (

// elements maps each layout element to its images.

elements = make(map[string][]*image.RGBA)

// backgroundImage contains the background image data.

backgroundImage *image.RGBA

// defaultImage is the image that is served if an error occurs.

defaultImage *image.RGBA

// loadOnce is used to call the load function only on the first request.

loadOnce sync.Once

)

// load reads the various PNG images from disk and stores them in their

// corresponding global variables.

func load() {

defaultImage = loadPNG(defaultImageFile)

backgroundImage = loadPNG(backgroundImageFile)

for dirKey, dir := range dirs {

paths, err := filepath.Glob(dir + "/*.png")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

for _, p := range paths {

elements[dirKey] = append(elements[dirKey], loadPNG(p))

}

}

}Requests are handled in a straightforward sequence:

- Parse the request URL, decoding the decimal value of each character in the path.

- Make a copy of the background image as the base for the final image.

- Draw each image element onto the background image using the layoutMap to determine where they should be drawn.

- Encode the image as a JPEG

- Return the image to user by writing the JPEG directly to the HTTP response writer.

Should any error occur, we serve the defaultImage to the user and log the error to the App Engine dashboard for later analysis.

Here's the code for the request handler with explanatory comments:

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// [[https://blog.golang.org/2010/08/defer-panic-and-recover.html][Defer]] a function to recover from any panics.

// When recovering from a panic, log the error condition to

// the App Engine dashboard and send the default image to the user.

defer func() {

if err := recover(); err != nil {

c := appengine.NewContext(r)

c.Errorf("%s", err)

c.Errorf("%s", "Traceback: %s", r.RawURL)

if defaultImage != nil {

w.Header().Set("Content-type", "image/jpeg")

jpeg.Encode(w, defaultImage, &imageQuality)

}

}

}()

// Load images from disk on the first request.

loadOnce.Do(load)

// Make a copy of the background to draw into.

bgRect := backgroundImage.Bounds()

m := image.NewRGBA(bgRect.Dx(), bgRect.Dy())

draw.Draw(m, m.Bounds(), backgroundImage, image.ZP, draw.Over)

// Process each character of the request string.

code := strings.ToLower(r.URL.Path[len(prefix):])

for i, p := range code {

// Decode hex character p in place.

if p < 'a' {

// it's a digit

p = p - '0'

} else {

// it's a letter

p = p - 'a' + 10

}

t := urlMap[i] // element type by index

em := elements[t] // element images by type

if p >= len(em) {

panic(fmt.Sprintf("element index out of range %s: "+

"%d >= %d", t, p, len(em)))

}

// Draw the element to m,

// using the layoutMap to specify its position.

draw.Draw(m, layoutMap[t], em[p], image.ZP, draw.Over)

}

// Encode JPEG image and write it as the response.

w.Header().Set("Content-type", "image/jpeg")

w.Header().Set("Cache-control", "public, max-age=259200")

jpeg.Encode(w, m, &imageQuality)

}For brevity, I've omitted several helper functions from these code listings. See the source code for the full scoop.

Performance

This chart - taken directly from the App Engine dashboard - shows average request latency during launch. As you can see, even under load it never exceeds 60 ms, with a median latency of 32 milliseconds. This is wicked fast, considering that our request handler is doing image manipulation and encoding on the fly.

Conclusions

I found Go's syntax to be intuitive, simple and clean. I have worked a lot with interpreted languages in the past, and although Go is instead a statically typed and compiled language, writing this app felt more like working with a dynamic, interpreted language.

The development server provided with the SDK quickly recompiles the program after any change, so I could iterate as fast as I would with an interpreted language. It's dead simple, too - it took less than a minute to set up my development environment.

Go's great documentation also helped me put this together fast. The docs are generated from the source code, so each function's documentation links directly to the associated source code. This not only allows the developer to understand very quickly what a particular function does but also encourages the developer to dig into the package implementation, making it easier to learn good style and conventions.

In writing this application I used just three resources: App Engine's Hello World Go example, the Go packages documentation, and a blog post showcasing the Draw package. Thanks to the rapid iteration made possible by the development server and the language itself, I was able to pick up the language and build a super fast, production ready, doodle generator in less than 24 hours.

Download the full app source code (including images) at the Google Code project.

Special thanks go to Guillermo Real and Ryan Germick who designed the doodle.

相关文章

- Announcing App Engine’s New Go 1.11 Runtime

- Go on App Engine: tools, tests, and concurrency

- Two recent Go articles

- The App Engine SDK and workspaces (GOPATH)

- Go updates in App Engine 1.7.1

- Go videos from Google I/O 2012

- Building StatHat with Go

- The Go Programming Language turns two

- Writing scalable App Engine applications

- Go App Engine SDK 1.5.5 released

- Two Go Talks: "Lexical Scanning in Go" and "Cuddle: an App Engine Demo"

- Go for App Engine is now generally available

- Go at Google I/O 2011: videos

- Go and Google App Engine

- Go at Heroku

- Real Go Projects: SmartTwitter and web.go

- Go at I/O: Frequently Asked Questions