Go 博客

Go fonts

2016/11/16

An Announcement

The experimental user interface toolkit being built at

golang.org/x/exp/shiny

includes several text elements, but there is a problem with testing them:

What font should be used?

Answering this question led us to today's announcement,

the release of a family of high-quality WGL4 TrueType fonts,

created by the Bigelow & Holmes type foundry specifically for the Go project.

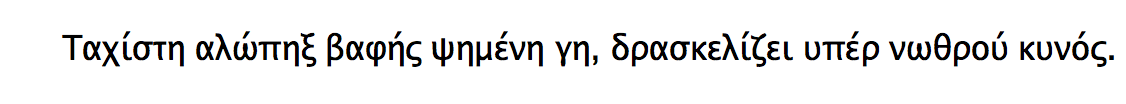

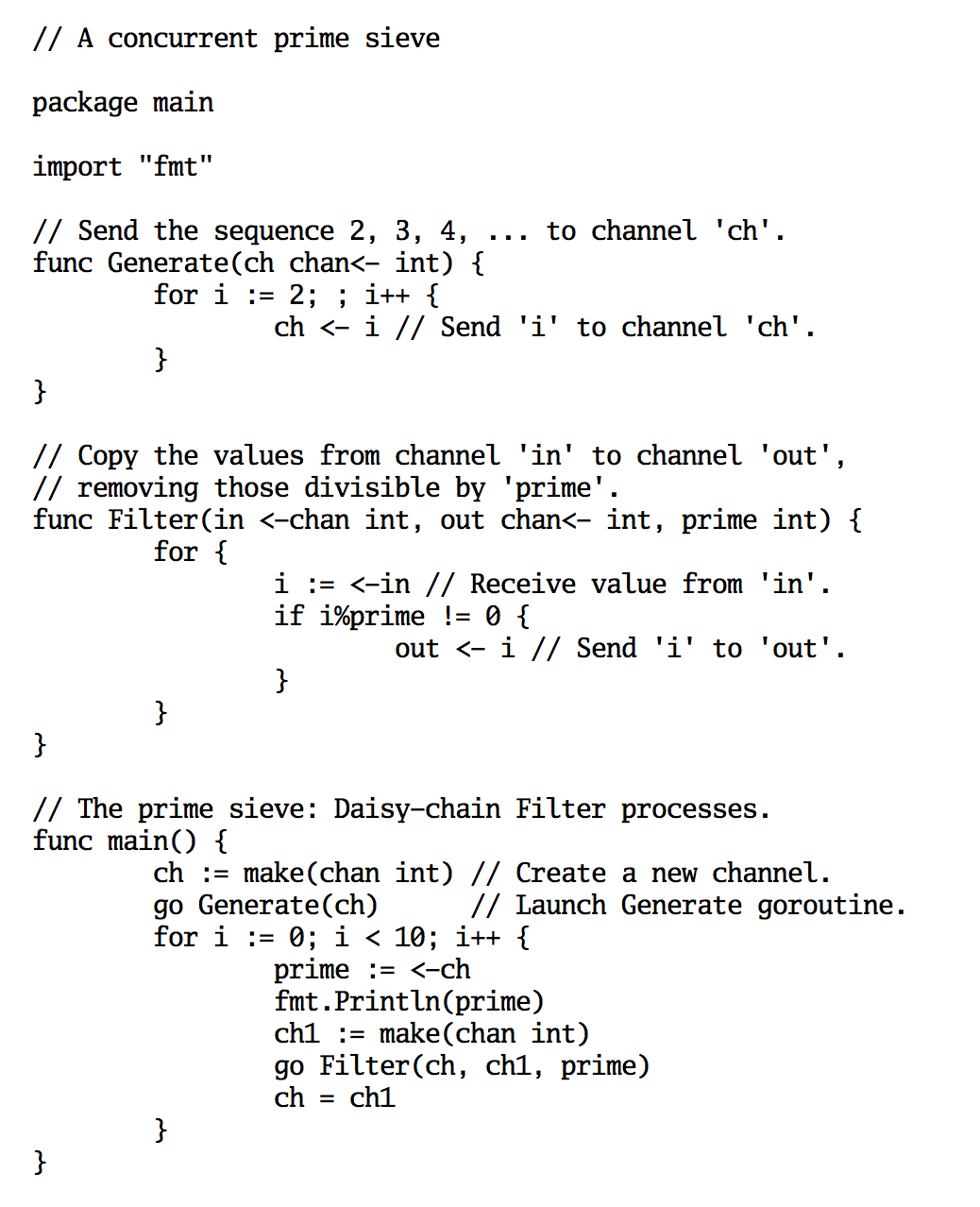

The font family, called Go (naturally), includes proportional- and fixed-width faces in normal, bold, and italic renderings. The fonts have been tested for technical uses, particularly programming. Go source code looks particularly good when displayed in Go fonts, as its name implies, with things like punctuation characters easily distinguishable and operators lined up and placed consistently:

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the Go fonts is their license: They are licensed under the same open source license as the rest of the Go project's software, an unusually free arrangement for a high-quality font set.

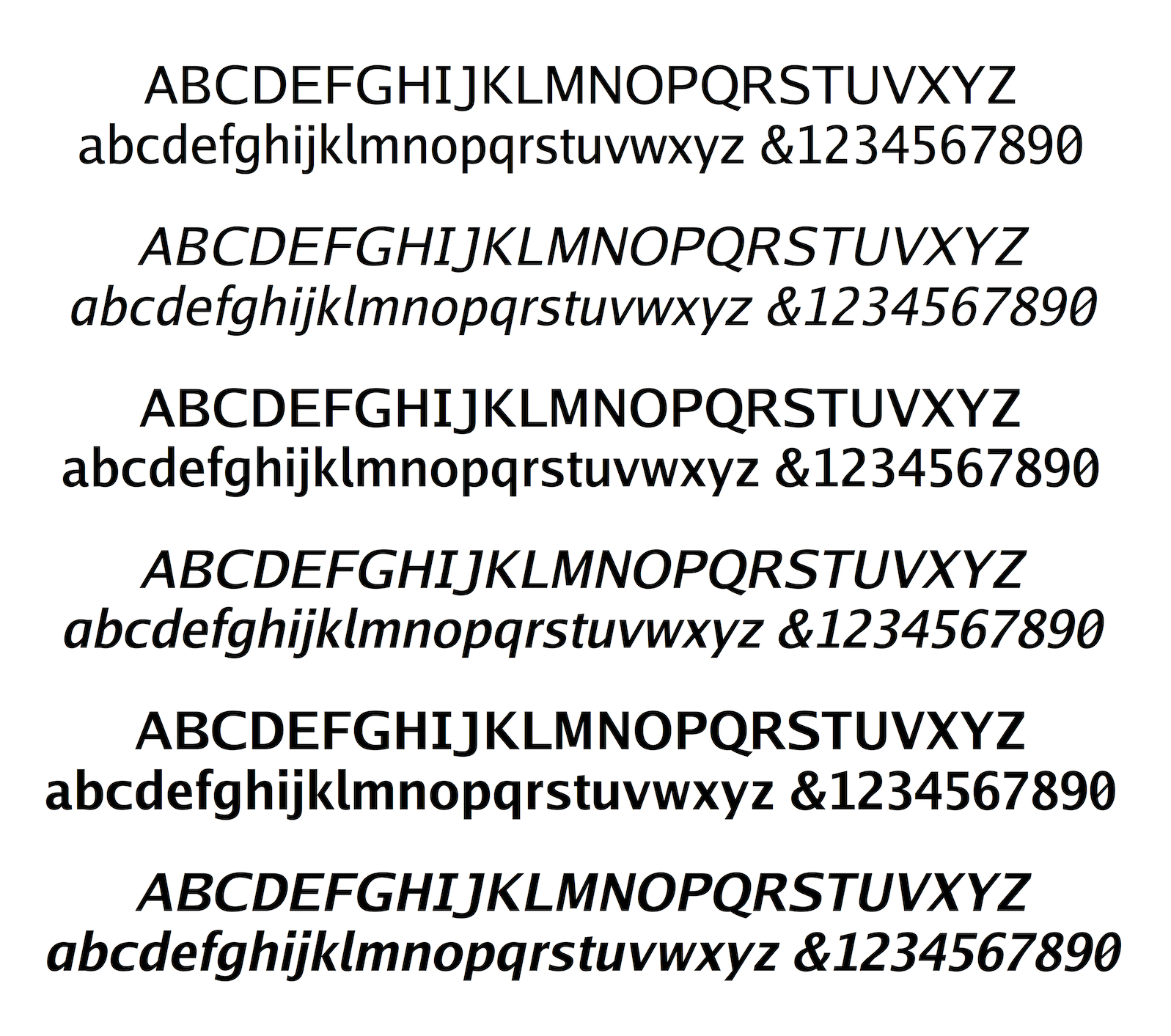

Here are samples of the proportionally-spaced...

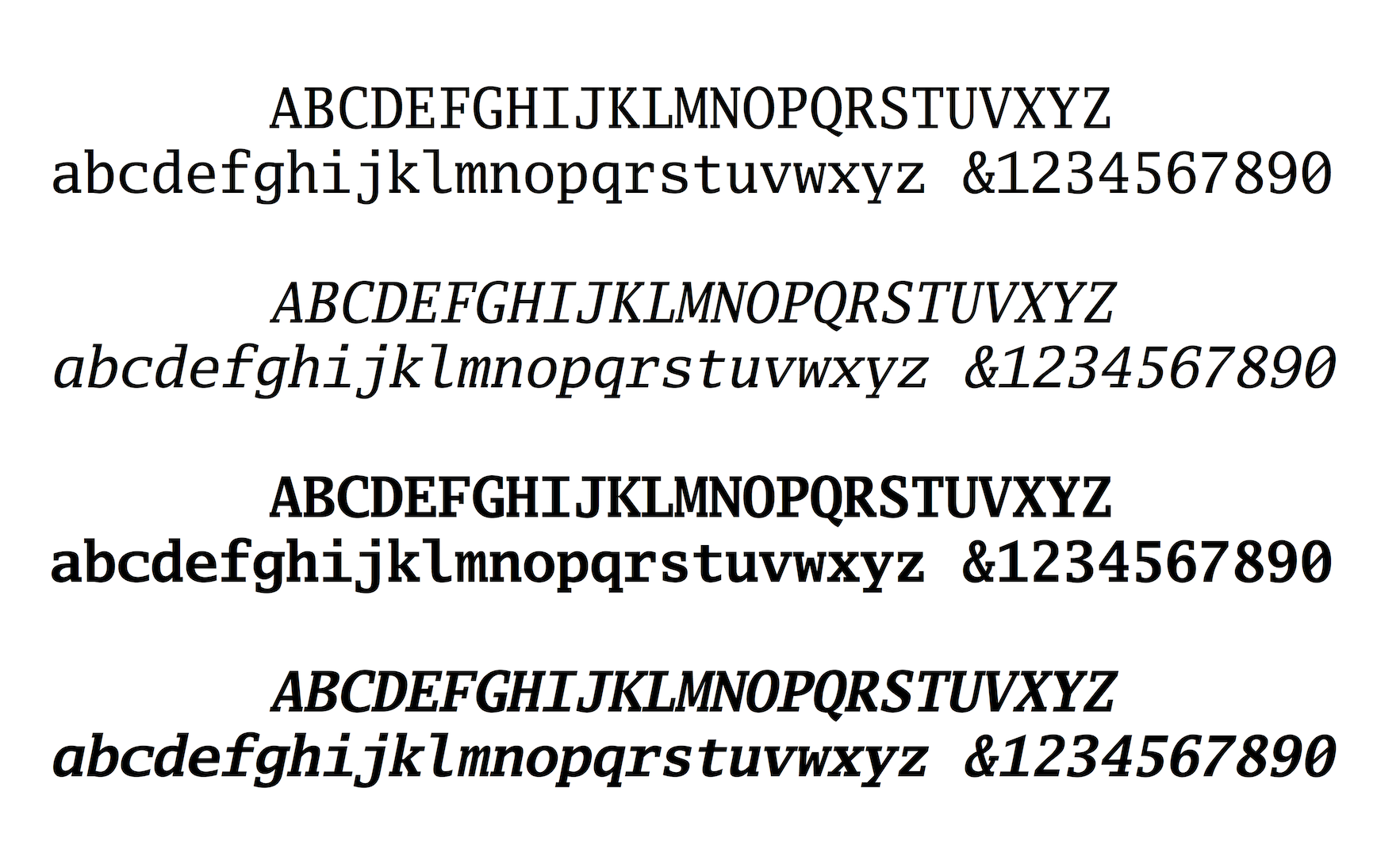

and monospaced fonts:

How to use them

If you just want the TTF files, run

git clone https://go.googlesource.com/image

and copy them from the subsequent image/font/gofont/ttfs directory.

If you want to use Go (the fonts) with Go (the software), each font is provided by a separate package.

To use the Go Regular font in a program, import golang.org/x/image/font/gofont/goregular, and write:

font, err := truetype.Parse(goregular.TTF)

The github.com/golang/freetype/truetype

package provides the truetype.Parse function today.

There is also work underway to add a TrueType package under golang.org/x

again licensed under the same open source license as the rest of the Go project's software.

We leave it to you to find some of the other unusual properties the fonts have, but for an overview of the fonts' design we asked Chuck Bigelow to provide some background. The remainder of this blog post is his response.

Notes on the fonts, by Chuck Bigelow

The Go fonts are divided into two sets, Go proportional, which is sans-serif, and Go Mono, which is slab-serif.

Go proportional fonts

Sans-serif

Go proportional fonts are sans-serif, like several popular fonts for screen displays. There is some evidence that some sans-serif faces at small sizes and low resolutions on screens are slightly more legible than their seriffed counterparts, while at large sizes, there is not a significant difference in legibility between sans and seriffed faces, at least in the pair tested. [1] (The bracketed numbers refer to the references listed at the end of this article.)

Style

Go sans-serif fonts are "humanist" rather than "grotesque" in style. This is an historical distinction, not an aesthetic judgment. Widely used sans-serif fonts like Helvetica and Arial are called grotesque because an early 19th century sans-serif typeface was named "Grotesque," and the name became generic.

The shapes of modern grotesque fonts like Helvetica are sculpted, with smooth, assimilated forms.

Humanist sans-serifs are derived from Humanist handwriting and early fonts of the Italian Renaissance and still show subtle traces of pen-written calligraphy. There is some evidence that humanist fonts are more legible than grotesque fonts. [2]

Italics

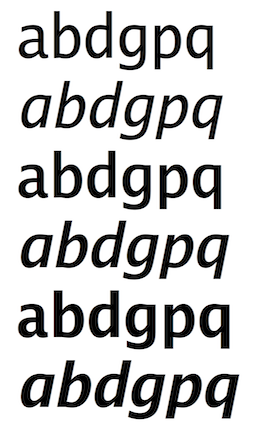

Go proportional italics have the same width metrics as the roman fonts. Go italics are oblique versions of the romans, with one noticeable exception: the italic lowercase 'a' is redesigned as a cursive single-story form to harmonize with the bowl shapes of the b d g p q set, in which the upright forms also adapt well to slanting, The addition of cursive 'a' makes the italics appear more lively than a simply slanted roman. Some typographers believe that slanted roman sans-serif italics are preferable to truly "cursive" sans Italics, in part because of history and design. [3]

The x-height

The x-height of a typeface is the height of the lowercase 'x' relative to the body size. The x-height of Go fonts is 53.0% of body size, a bit larger than the x-heights of Helvetica (52.3%) or Arial (51.9%), but the difference is usually unnoticeable at normal reading sizes. Typographers believe that larger x-heights contribute to greater legibility in small sizes and on screens. A study of "print size" (particularly x-height) and reading noted that types for reading on screens and for small sizes tend to have large x-heights. [4]

DIN Legibility Standard

The recent German DIN 1450 legibility standard recommends several features for font legibility, including differentiation of letter shapes to reduce confusion. The Go fonts conform to the 1450 standard by carefully differentiating zero from capital O; numeral 1 from capital I (eye) and lowercase l (ell); numeral 5 from capital S; and numeral 8 from capital B. The shapes of bowls of b d p q follow the natural asymmetries of legible Renaissance handwriting, aiding differentiation to reduce confusion. [5]

Weights

The Go proportional fonts come in three weights: Normal, Medium, and Bold. The Normal weight is strong enough that it maintains clarity on backlit screens, which often tend to erode letter features and thickness. The Medium weight has stem thickness 1.25 times the Normal, for greater sturdiness on bright screens or for users who prefer a sturdy font. The Bold weight has stem thickness 1.5 times the Normal, bold enough to be distinct from the normal weight. These Go fonts have CSS numerical weights of 400, 500, and 600. Although CSS specifies "Bold" as a 700 weight and 600 as Semibold or Demibold, the Go numerical weights match the actual progression of the ratios of stem thicknesses: Normal:Medium = 400:500; Normal:Bold = 400:600. The Bold weight name matches the use of “Bold” as the usual corresponding bold weight of a normal font. More discussion of the relationship of stem thicknesses, weight names, and CSS numbering is in [6].

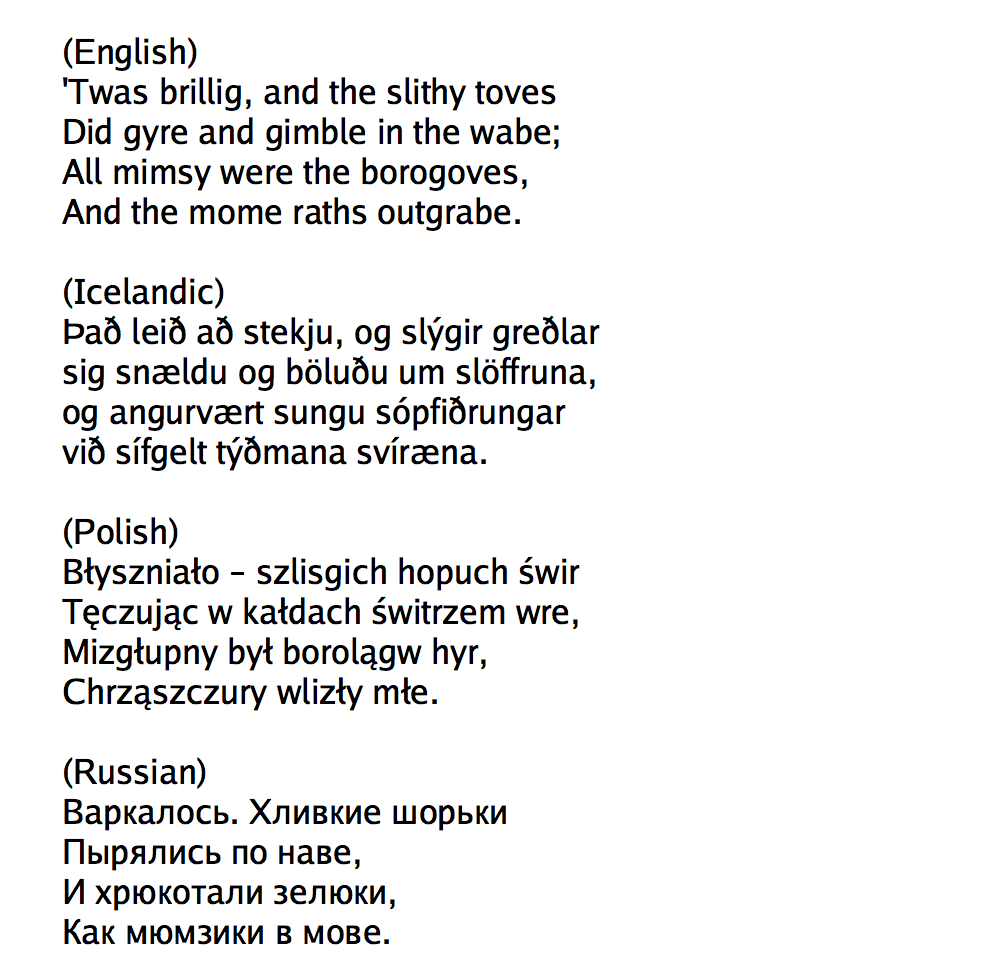

WGL4 character set

The WGL4 character set, originally developed by Microsoft, is often used as an informal standard character set. WGL4 includes Western and Eastern European Latin characters plus Modern Greek and Cyrillic, with additional symbols, signs, and graphical characters, totalling more than 650 characters in all. The Go WGL4 fonts can be used to compose a wide range of languages. [7]

Metric compatibility with Arial and Helvetica

The Go sans-serif fonts are nearly metrically compatible with standard Helvetica or Arial characters. Texts set in Go occupy nearly the same space as texts in Helvetica or Arial (at the same size), but Go has a different look and texture because of its humanist style. Some Go letters with DIN legibility features are wider than corresponding letters in Helvetica or Arial, so some texts set in Go may take slightly more space.

Go Mono fonts

Monospaced

Go Mono fonts are monospaced—each letter has the same width as the other letters. Monospaced fonts have been used in programming since the beginning of computing and are still widely used because the typewriter regularity of their spacing makes text align in columns and rows, a style also found in Greek inscriptions of the 5th century BC. (The ancient Greeks didn't have typewriters or computer keyboards, but they did have great mathematicians and a great sense of symmetry and pattern that shaped their alphabet.)

Slab-serif

The Go Mono fonts have slab-shaped serifs, giving them a sturdy appearance.

Style

The underlying letter shapes of Go Mono are, like the Go sans-serif fonts, derived from humanist handwriting, but the monospacing and slab serifs tend to obscure the historical and stylistic connections.

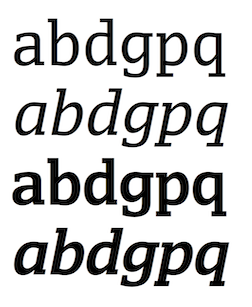

Italics

Go Mono Italics are oblique versions of the romans, with the exception that the italic lowercase 'a' is redesigned as a cursive single-story form to harmonize with the bowl shapes of the b d g p q. The cursive 'a' makes the italics appear more lively than a simply slanted roman. As with many sans-serif fonts, it is believed that slanted roman slab-serifs fonts may be more legible than truly "cursive" italics.

The x-height

Go Mono fonts have the same x-height as Go sans-serif fonts, 53% of the body size. Go Mono looks almost 18% bigger than Courier, which has an x-height 45% of body size. Yet Go Mono has the same width as Courier, so the bigger look is gained with no loss of economy in characters per line.

DIN Legibility Standard

Go Mono fonts conform to the DIN 1450 standard by differentiating zero from capital O; numeral 1 from capital I (eye) and lowercase l (ell); numeral 5 from capital S; and numeral 8 from capital B. The shapes of bowls of b d p q follow the natural asymmetries of legible Renaissance handwriting, aiding differentiation and reducing confusion.

Weights

Go Mono fonts have two weights: Normal and Bold. The normal weight stem is the same as in Go Normal and thus maintains clarity on backlit screens, which tend to erode letter features and stem thickness. The bold stem thickness is 1.5 times thicker than the normal weight, hence the Bold Mono has the same stem thickness as Bold Go proportional. Because the letter width of monospaced bold is identical to the width of monospaced normal, the bold Mono appears slightly bolder than the proportional Go Bold, as more black pixels are put into the same area.)

Metric compatibility with popular monospaced fonts

Go Mono is metrically compatible with Courier and other monospaced fonts that match the "Pica" typewriter type widths of 10 characters per linear inch at 12 point. At 10 point, Go Mono fonts set 12 characters per inch. The TrueType fonts are scalable, of course, so Go Mono can be set at any size.

WGL4 character set

The Go Mono fonts offer the WGL4 character set often used as an informal standard character set. WGL4 includes Western and Eastern European Latin characters plus Modern Greek and Cyrillic, with additional symbols, signs, and graphical characters. The 650+ characters of the Go WGL4 sets can be used for a wide range of languages.

References

[1] Morris, R. A., Aquilante, K., Yager, D., & Bigelow, C. (2002, May). P‐13: Serifs Slow RSVP Reading at Very Small Sizes, but Don't Matter at Larger Sizes. In SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers (Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 244-247). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

[2] Bryan Reimer et al. (2014) “Assessing the impact of typeface design in a text-rich automotive user interface”, Ergonomics, 57:11, 1643-1658. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00140139.2014.940000

[3] Adrian Frutiger - Typefaces: The Complete Works. H. Osterer and P. Stamm, editors. Birkhäuser, Basel, 2009, page 257.

[4] Legge, G. E., & Bigelow, C. A. (2011). Does print size matter for reading? A review of findings from vision science and typography. Journal of Vision, 11(5), 8-8. http://jov.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2191906

[5] Charles Bigelow. "Oh, oh, zero!" TUGboat, Volume 34 (2013), No. 2. https://tug.org/TUGboat/tb34-2/tb107bigelow-zero.pdf https://tug.org/TUGboat/tb34-2/tb107bigelow-wang.pdf

[6] "Lucida Basic Font Weights" Bigelow & Holmes. http://lucidafonts.com/pages/facts

[7] WGL4 language coverage: Afrikaans, Albanian, Asu, Basque, Belarusian, Bemba, Bena, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Catalan, Chiga, Colognian, Cornish, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Embu, English, Esperanto, Estonian, Faroese, Filipino, Finnish, French, Friulian, Galician, Ganda, German, Greek, Gusii, Hungarian, Icelandic, Inari Sami, Indonesian, Irish, Italian, Jola-Fonyi, Kabuverdianu, Kalaallisut, Kalenjin, Kamba, Kikuyu, Kinyarwanda, Latvian, Lithuanian, Lower Sorbian, Luo, Luxembourgish, Luyia, Macedonian, Machame, Makhuwa-Meetto, Makonde, Malagasy, Malay, Maltese, Manx, Meru, Morisyen, North Ndebele, Northern Sami, Norwegian Bokmål, Norwegian Nynorsk, Nyankole, Oromo, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Romansh, Rombo, Rundi, Russian, Rwa, Samburu, Sango, Sangu, Scottish Gaelic, Sena, Serbian, Shambala, Shona, Slovak, Slovenian, Soga, Somali, Spanish, Swahili, Swedish, Swiss German, Taita, Teso, Turkish, Turkmen, Upper Sorbian, Vunjo, Walser, Welsh, Zulu

Jabberwocky in Go Regular

From en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jabberwocky:

There is no Greek version listed. Instead, a pangram from clagnut.com/blog/2380/#Greek: